The older you get, the harder it is to change your perspective on the world. Part of this is because of the repetition that seems to be a hallmark of adult life. Every day, you get up, go to work and come home, and you only get a small portion of each day to yourself outside of weekends. That forces you to do rote tasks like grocery shopping, cleaning, laundry, exercising, caring for children and/or pets if you have them, and attending to myriad other daily activities in whatever free time you have left, leaving precious little time to do leisurely things like read, walk, watch films or television, travel, socialize, etc. Thus, your daily routine becomes firmly entrenched and it becomes harder and harder to think about the world in a way that doesn’t fit in with your daily, monotonous adult life. Changing your perspective on the world becomes more and more difficult the deeper you sink into your routine and many adults find themselves getting stuck in a rut, often becoming more conservative over time because they’re no longer exposed to or open to new experiences that introduce to new, perspective-changing people, places and things. They have the blinders on and can’t see past their own feet.

David Foster Wallace does a better job of articulating the above point than I can in his commencement speech known as This Is Water As DFW says in the speech, breaking this mold can be extraordinarily difficult. In order to be more pliable people, we just need to make sure that we keep ourselves open over time in order to maintain an empathetic world view in which we’re capable of changing our perspectives. Not always easy in a world where somebody cuts you off in traffic, the grocery store line is long, the train is late, and so on.

There is, of course, a shortcut to changing your perspective on the world. Some psychedelic drugs can open up different ways of perceiving the world. Psychedelic drugs are a quick and relatively painless way to experience the world in a dramatically different way than normal. If your daily life is repetitive, unchanging and stale and you see the world as solid and unchanging, then taking a substance which causes the walls and floors around you to bend and vibrate and makes you see colors and shapes that you don’t typically see should help to change your perspective on the nature of reality.

However, the more traditional ways that have not included the use of drugs have been some of the methods mentioned above. Simple things like reading, exploring the world, traveling and socializing with others (especially those who aren’t like me or my peer group) have been instrumental in helping me see the world from a fresh perspective over time.

I recently traveled to Berlin and while there, took a day trip to Dessau to see the Bauhaus. I bought an old copy of the Bauhaus’s magazine – an issue about photography at the Bauhaus, of course – and read an article that talked about the multimedia artist and educator Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. Moholy-Nagy was an interesting character. I never knew anything about him until this trip, but once I learned more about the Bauhaus and him in particular, I became fascinated. There’s a great documentary about him and his lasting impact on design and photography that’s very worth watching. In any event, this article mentioned how Moholy-Nagy and some of the other Bauhaus instructors (Andreas and T. Lux Feininger) were interested in using photographs to subvert traditional perspectives on art and the world. Photography was only approximately 50 years old at the time, but the 35mm film roll was an especially new medium when the Bauhaus was operating from 1919 until 1933. The 135 film format was slowly becoming adopted by the mid 1920’s, though it had existed in some way for about 10 years. Its mass adoption coincided with the first mass-produced Leica cameras, which were introduced in Germany around 1926-27.

I’ve become more interested in Moholy-Nagy’s photography. Compared to today’s image-saturated culture, his optimism for what photography could be and how it could be used to create modern art on a mass scale are refreshing and represent what separates photography from other mediums to me. The Bauhaus was primarily focused on designing for the new, industrial age. Mostly headed up by veterans of WWI, they were interested in a new architecture and design aesthetic that would be free of decoration and historical associations (the trappings of old Europe). Instead, a new design aesthetic was needed for the industrial age that more accurately represented the modern world and could be adopted on a mass scale to create a better life for ordinary people. The photograph, in that respect, was the perfect medium to complement the Bauhaus, because it was a new technology, created using a streamlined industrial process. Instead of being made with ancient materials like paint, marble or instruments, the photograph was created with a complicated piece of machinery and a strip that only made sense of the world after being exposed to chemicals and printed. It was the quintessential industrial art.

More than just industrial art, however, the photograph is also a portal into the way somebody else sees the world. Sometimes this isn’t so obvious, but when you look at the photographs of a great photographer, you know that something special is happening within the four borders of their frame. A small slice of reality has been imprinted onto the piece of film. The photographer may have stood for hours waiting to take the photograph, or may have snapped it quickly while on their way somewhere, or may have scoped out a location and photographed it a million times before they took the picture that impacted you in the way that it did.

Of course, the photograph, in the form of the Leica and 35mm film roll, could also be put into the hands of anybody. It was portable and didn’t take much expertise to be done well. It didn’t necessarily take years of training and development to be a good photographer – all it took was a good eye and an ability to press the shutter at the right moment. And the results of a good photograph were especially impactful – in a way that seemed to indicate to the Bauhauslers that it would become the primary form of art for the 20th century and beyond.

In many ways, that prophecy came true. Photography became an incredibly important part of popular culture fairly quickly after the invention of the Leica and the motion picture. Photography is a powerful medium, especially when combined with time and sound. It would be hard to say whether any other art form was more dominant in the 20th century, and certainly in the “post-modern” 21st century (French philosopher Jean Baudrillard made the argument in Simulacra and Simulation as early as the 1980’s that Western society is so saturated with images that it’s actually now impossible to look at an image and see the reality behind the image – at this point, we see image first, reality second). This speaks to the special power of photography as a medium. I took a class on aesthetic philosophy in college and my professor, Robert Hopkins, was especially interested in the idea of why motion pictures seem to be so much more captivating than almost any other form of art. David Foster Wallace, who eschewed having a television in his house because he found it too addicting, would say he was on to something.

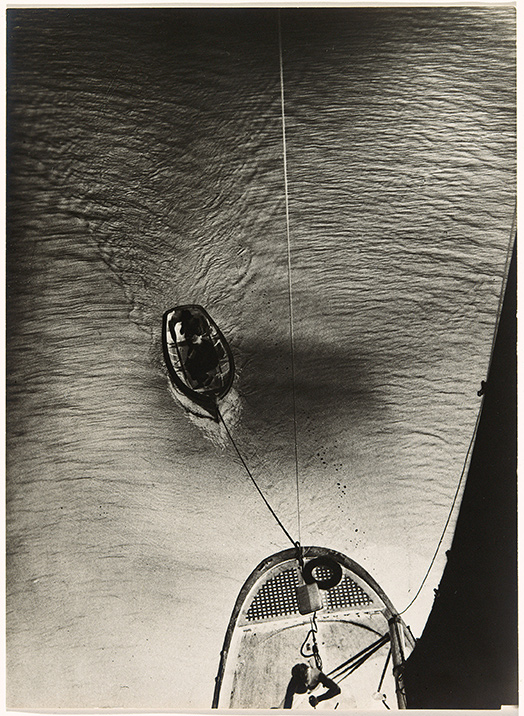

At its core, however, the photograph is simply an impression of the world. It’s been a while since I’ve been stopped in my tracks at another’s impression of the world. The last great photographer to do that for me was W. Eugene Smith (though my obsession with his work might have something to do with the fact that his work doubles as a sort of historical record of one of my favorite cities – Pittsburgh). Moholy-Nagy’s work, on the other hand, holds little historical/personal significance to me and yet was arresting the first time I saw it, because his perspective was so unique and his personality came through the camera in such an obvious way. His photographs struck me as very playful and exploratory and his enthusiasm for the potential of photography as a medium is so essential to the way his photographs look.

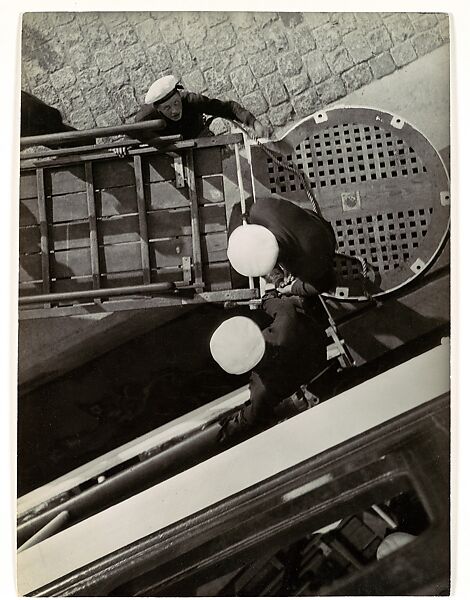

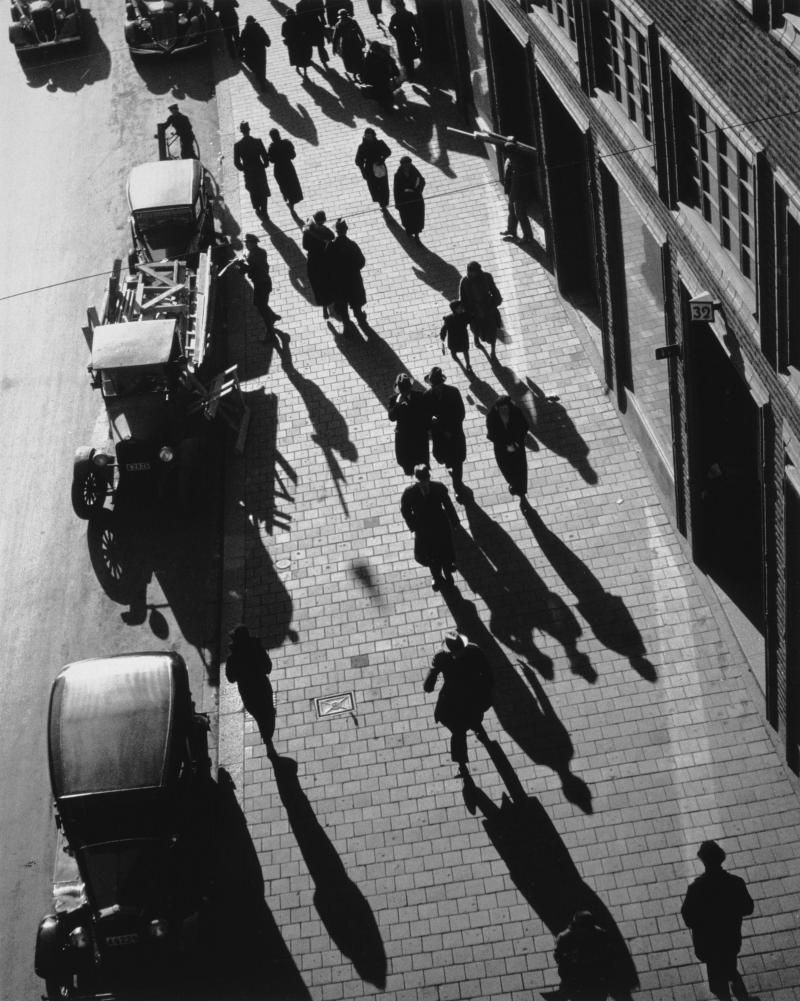

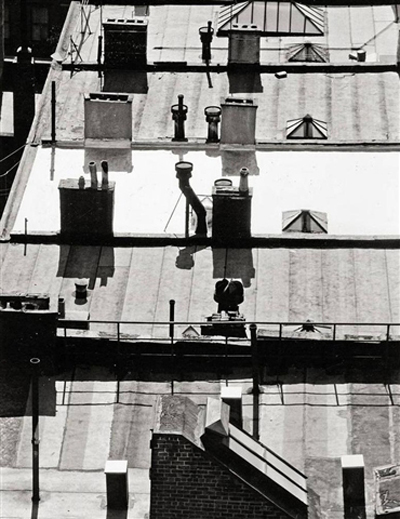

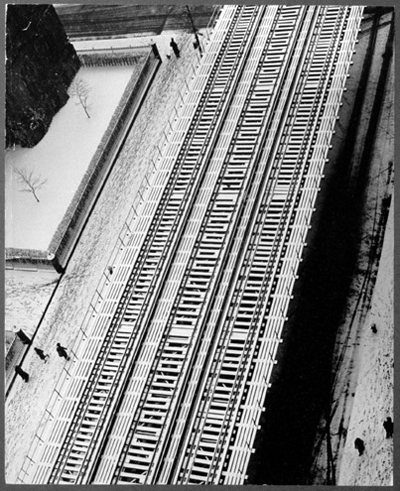

One thing that’s quite obvious in his photographs is how he plays with perspective. Often looking up or, more interestingly, looking down, Moholy-Nagy is often looking at the world in a way that you might not have thought to look at it in your everyday life, or subverting traditional perspectives as the magazine article stated. His frames often remind me of some of the scenes I love so much from early film noir – the ferris wheel scene and sewer sequence from The Third Man, the disorienting and chaotic mirror sequence in The Lady From Shanghai, or the use of lower perspectives in The Maltese Falcon to portray certain characters as intimidating or powerful. In all film noir, the ever-present elements of light and shadow are as important to the story as the plot and serve to set the mood. For Moholy-Nagy, light was an equally important component of a strong photograph.

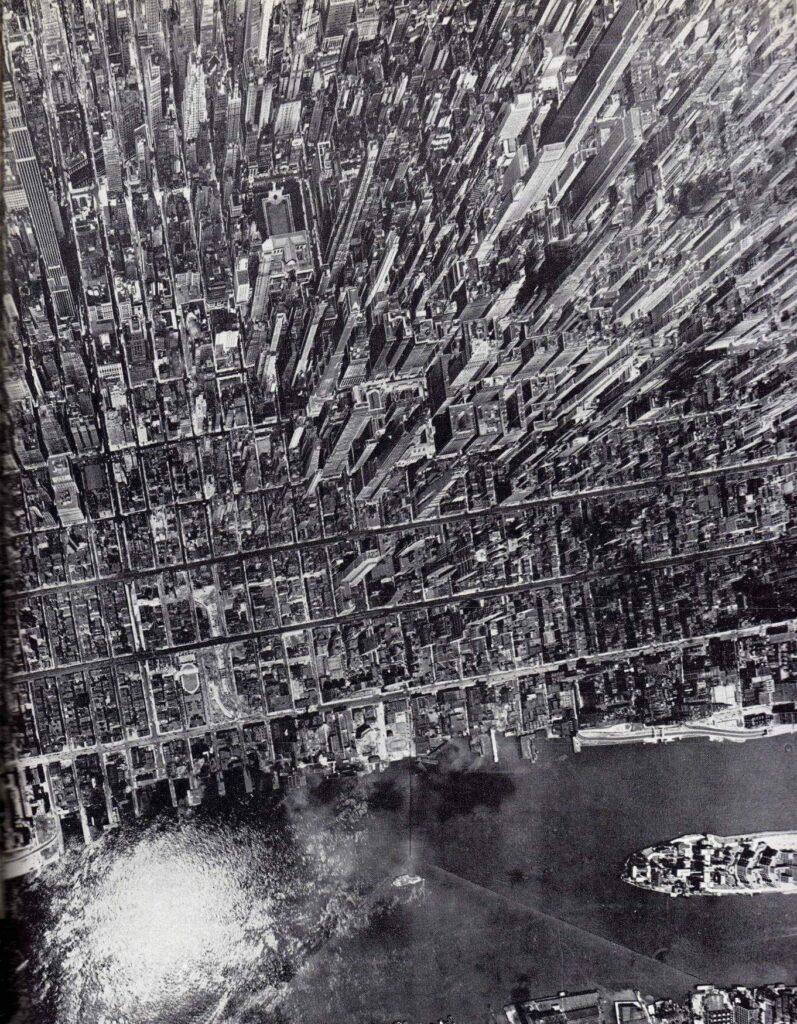

Andreas Feininger’s photographs of New York show similar changes of perspectives. Like many Bauhaus instructors, Feininger fled Germany during the Nazi occupation and came to America looking for new work. He landed in New York and took photographs during the city’s rapid development in the 1940’s. Similar to Moholy-Nagy, he is often looking up or looking down, exploring every nook and cranny of the city, clearly enthused with the energy of New York and thrilled by the tall buildings of the new, modern world.

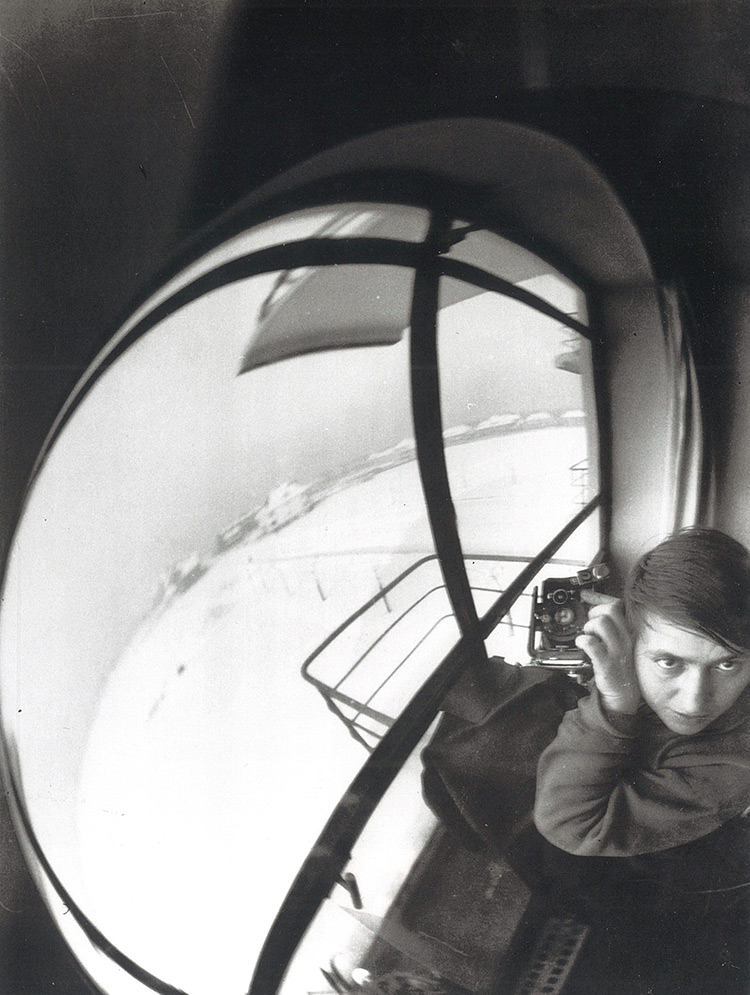

Marianne Brandt also took photographs during her time at the Bauhaus that were strong exemplars of a change in perspective. Her reflection photos are precursors to the now-ubiquitous mirror selfie. Several of her photographs show her self-portrait taken into large, mirrored balls, a favorite design piece of the Bauhaus. However, her photos are wonderfully devoid of any of the post-modern irony of the way people now photograph themselves in mirrors and are simply enthusiastic about the way that the mirrored ball looks and how it rendered her portrait – radically different from traditional oil painting portraits or marble sculptures. There is nothing traditional about these portraits – they are thoroughly modern in their use of new medium, materials and expression, and yet lacking in the excessive self-awareness that often makes post-modern art boring. There is no third wall in between the photographer and the mirror, no element of “look at me looking at me”. Rather, the message reads “wow, look at how cool this is!”.

The Bauhaus photographs were all about shifting perspective. I’ve tried to incorporate different angles into my photography for several years now. I used to be inspired by Stephen Shore’s Uncommon Places, and the large format, straight ahead photographs of the New Topographics movement, but in recent years, I’ve taken much more inspiration from film noir, motion pictures in general, and now from the photographs of the Bauhauslers and other early 20th century photographers. I find shifting perspective to be more fun and to make photography more of an adventure and a challenge, which I welcome in my everyday life. Moreover, shifting perspectives are a more aspirational way to depict the world around me – they help to shape my world view and inform the way I interact with things and people around me. Shifting perspectives in my photographs helps me to think outside of my own world in everyday life.

To get back to the original point of this piece, it’s hard to shift your perspective as an adult. I still struggle frequently with getting myself out of my own box, both in daily life and in my photography, but trying to make time for the things that help to change your perspective – new social interactions, reading, traveling, etc. always helps. Traveling to the Bauhaus has certainly helped to shift my perspective on photography and art in general, and has invigorated me in redesigning my house, building new furniture, and refreshing my life overall after a period of little change. The world is a beautiful place and looking at it differently can transform your daily enjoyment of life. The first lesson that Moholy-Nagy taught his students in his Art Institute of Chicago (he, too moved to America after the Nazi occupation) was to carve something tactile out of wood. It didn’t matter what it was – the piece didn’t have to have any purpose, it just had to feel good in the hands. It was a fitting lesson – take a solid material, like wood, which comes in sheets and blocks, and carve something out of it that feels good in the hands – in other words, change your perspective and forget everything you know about the material, then you’ll be ready to begin learning.